This policy brief is a collaborative effort based on data analysis and research discussion among the following researchers affiliated with the Research Consortium on Education Policy and Development in the Greater Bay Area (RECEPD), HKIER:

Dr. Dongshu OU

Dr. Kenneth K. WONG

Dr. Yuanyuan LIUHong Kong has been greatly influenced by immigration, with most of its population tracing their origins back to mainland China. However, as of 2021, approximately 8% of the population comprises individuals whose origins can be traced to countries other than China [1]. Throughout its colonial history, the British colonial government recruited individuals from Western countries as well as South and Southeast Asia for civil service or attracted them to seek business and employment opportunities during the industrialization period [2]. Many of these immigrants have their descendants born and raised in Hong Kong. However, due to the colonial government’s lack of emphasis on teaching Chinese/Cantonese as a second language, these immigrants and their descendants often have limited Chinese/Cantonese language proficiency [3].

Following the handover of sovereignty of Hong Kong back to China in 1997, the government implemented a mother tongue (Chinese/Cantonese) medium of instruction policy in primary and secondary schools. This policy placed students who did not speak Chinese/Cantonese and lacked financial resources to attend international schools at a disadvantage in terms of receiving quality education and achieving academic success in Hong Kong.

Since the early 2000s, the government has invested significant financial resources and implemented various measures to assist non-Chinese speaking (hereafter, NCS) students in learning Chinese and integrating into government-funded schools. However, there have been concerns regarding the vagueness of the government’s guidelines and ongoing debates among non-governmental organizations and academics about the best practices for supporting NCS students [5]. Surprisingly, there has been no systematic research documenting the trend of the academic performance of NCS students from 2000 onwards.

This policy brief focuses on documenting the trend and potential determinants of NCS students’ underachievement relative to their peers (specifically, locally-born Chinese-speaking students whose parents are also locally-born) using data from the 2003-2022 waves of the Program of International Student Assessment (PISA)’s Hong Kong study. Since the Education Bureau defines students whose spoken language at home is not Chinese as NCS students when making educational support policies, we will also use this criterion to define NCS students in our study. However, it is important to note that many previous studies have primarily focused on the educational disadvantages faced by non-Chinese ethnic minority students in Hong Kong. Since most non-Chinese ethnic minority individuals do not speak Chinese/Cantonese at home (around 80% according to the 2016 Hong Kong census), the non-Chinese ethnic minority population and the NCS population represent two distinct but overlapping groups. Therefore, it is crucial to exercise caution when applying research results from one population to describe the situation of the other.

PISA is conducted on a tri-annual basis. In each participating country or territory (except for Russia), it employs a two-stage stratified sample design. In the first stage, nationally or territory-wide representative samples of schools are selected from a comprehensive list of all schools with 15-year-old students enrolled. In the second stage, a random sample of 35 to 42 students is selected from each sampled school.

For our analytic sample, we will exclude students enrolled in private international schools in Hong Kong. These schools are not eligible for government funding, and we can identify them through the PISA questionnaires administered to school principals. The questionnaire asked the principals to provide the percentage of their school’s funding that comes from the government. If the principal’s response to this question was 0%, then these schools are classified as private international schools. Although Hong Kong has participated in PISA since 2000, we will not use the 2000 wave of the PISA Hong Kong survey because it did not include a survey question about students’ usual language spoken at home.

Based on our sample restriction criteria, our final analytic sample yields the following student group distribution by survey year. NCS students account for approximately 1.3% – 4.9% of the government-funded student population body from 2003 to 2022 (see Table 1).

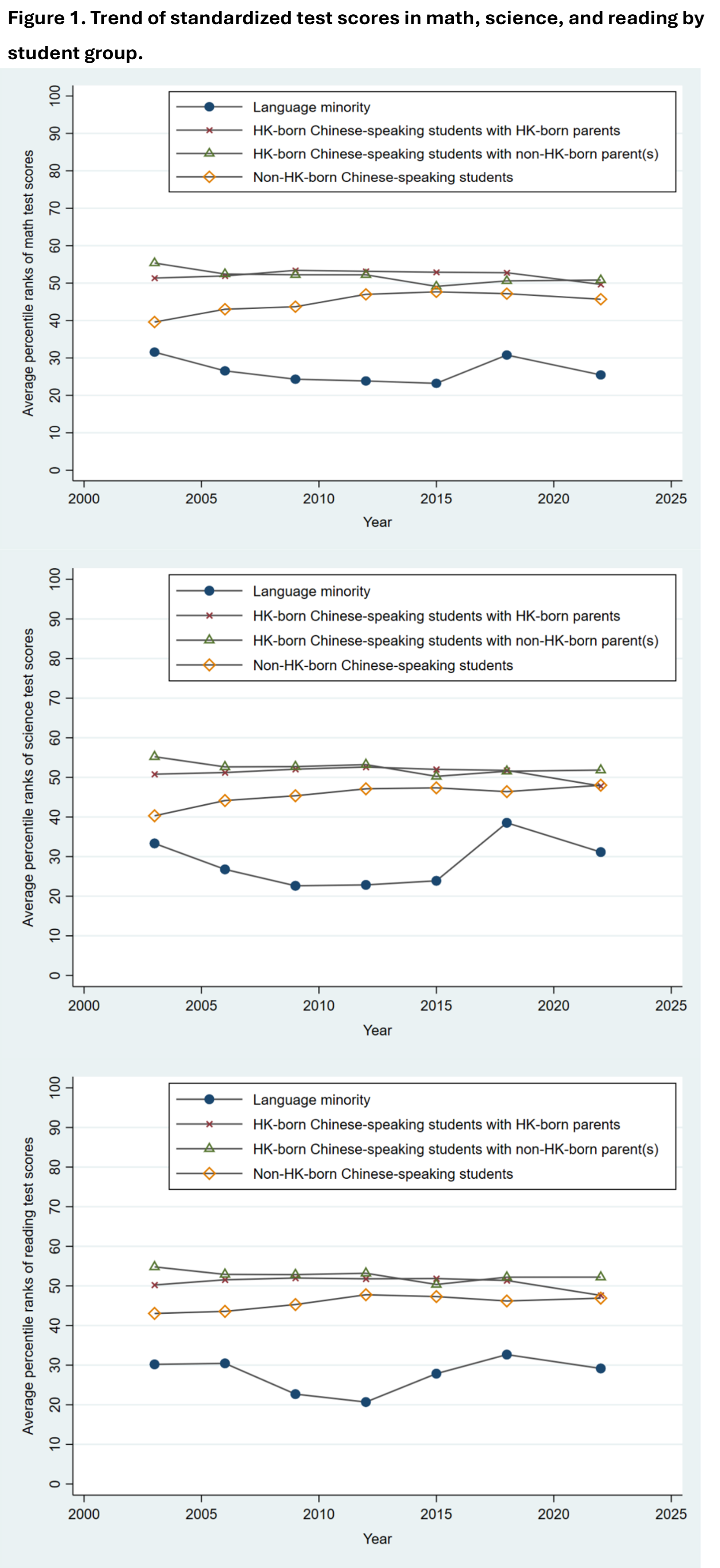

We first analyse the trends of the average test scores in math, science, and reading for the following student groups:

(1) Non-Chinese speaking (NCS) students;

(2) Hong Kong-born Chinese-speaking students with Hong Kong-born parents;

(3) Hong Kong-born Chinese-speaking students with at least one non-Hong Kong-born parent;

(4) Non-Hong Kong-born Chinese-speaking students.

Next, we analyse the trends of potential explanatory factors that may contribute to the observed trends in test scores. We conduct statistical tests to compare the differences in test scores and their predictors between NCS students and Hong Kong-born Chinese-speaking students with Hong Kong-born parents. The results of these statistical analyses can be found in the online supplementary tables accompanying this policy brief.

The PISA dataset provides 5 to 10 plausible values for the math, science, and reading test scores of each individual student, depending on the survey wave. These plausible values are randomly drawn from the estimated distribution of a latent construct representing the students’ underlying math, science, and reading abilities [6]. In this policy brief, we have employed the first plausible value from the students’ math, science, and reading tests for our analyses.

To ensure the comparability of students’ test scores across different PISA survey waves, we have used the percentile rank of each student within their respective survey year in our analysis of trends [7]. Calculating the percentile rank of students’ scores, rather than using the raw test scores, allows us to account for any potential changes in the difficulty or scaling of the PISA assessments over the years. By positioning each student’s performance relative to their peers within the same assessment year, we can effectively track the relative academic standing of NCS students in Hong Kong compared to their counterparts over the study periods.

According to Figure 1, the average test scores of NCS students exhibited a decline in all three test domains from 2003 to 2012. However, there was a recovery in scores between 2012 and 2018, followed by another decline from 2018 to 2022. Conversely, the average test scores of the other three groups remained relatively stable throughout the entire study period. Our statistical tests reveal that NCS students consistently obtained significantly lower test scores in all three domains compared to their locally born Chinese-speaking peers whose parents are also locally born, in the years 2003, 2012, 2018, and 2022. Furthermore, the observed changes in the disparities between the two student groups in terms of the test scores in all three domains from 2003 to 2012, as well as the gaps in science and reading test scores from 2003 to 2012 and from 2012 to 2018, are statistically significant.

The patterns depicted in Figure 1 align with three significant events that took place in specific years: 2004, 2014, and 2020. The period from 2003 to 2012 encompasses the year 2004, while the period from 2012 to 2018 covers 2014, and the period from 2018 to 2022 includes 2020. These events are as follows:

(1) In 2004, NCS students were integrated into the central allocation system for school enrollment, like their Chinese-speaking counterparts. However, the Education Bureau did not provide substantial targeted resources to support the integration of NCS students into local mainstream schools.

(2) In 2014, the Education Bureau implemented the “Chinese Language Curriculum Second Language Learning Framework” in primary and secondary schools. This framework aimed to assist students who faced challenges with the standard Chinese curriculum. Considerable financial resources were allocated to aid the integration of NCS students during this period.

(3) The global COVID-19 pandemic occurred in 2020, affecting various aspects of society. NCS students, who have historically encountered socio-cultural disadvantages, may have become more vulnerable to the impact of the pandemic compared to their locally born Chinese-speaking peers.

These events provide a contextual background for the observed patterns in Figure 1. In our subsequent analysis of potential factors that may explain the differences in academic achievement between NCS students and their locally born Chinese-speaking peers whose parents are also locally born, we will specifically examine the three time periods: 2003-2012, 2012-2018, and 2018-2022.

Key Predictors of the Achievement Gaps between NCS Students and Chinese-speaking Peers

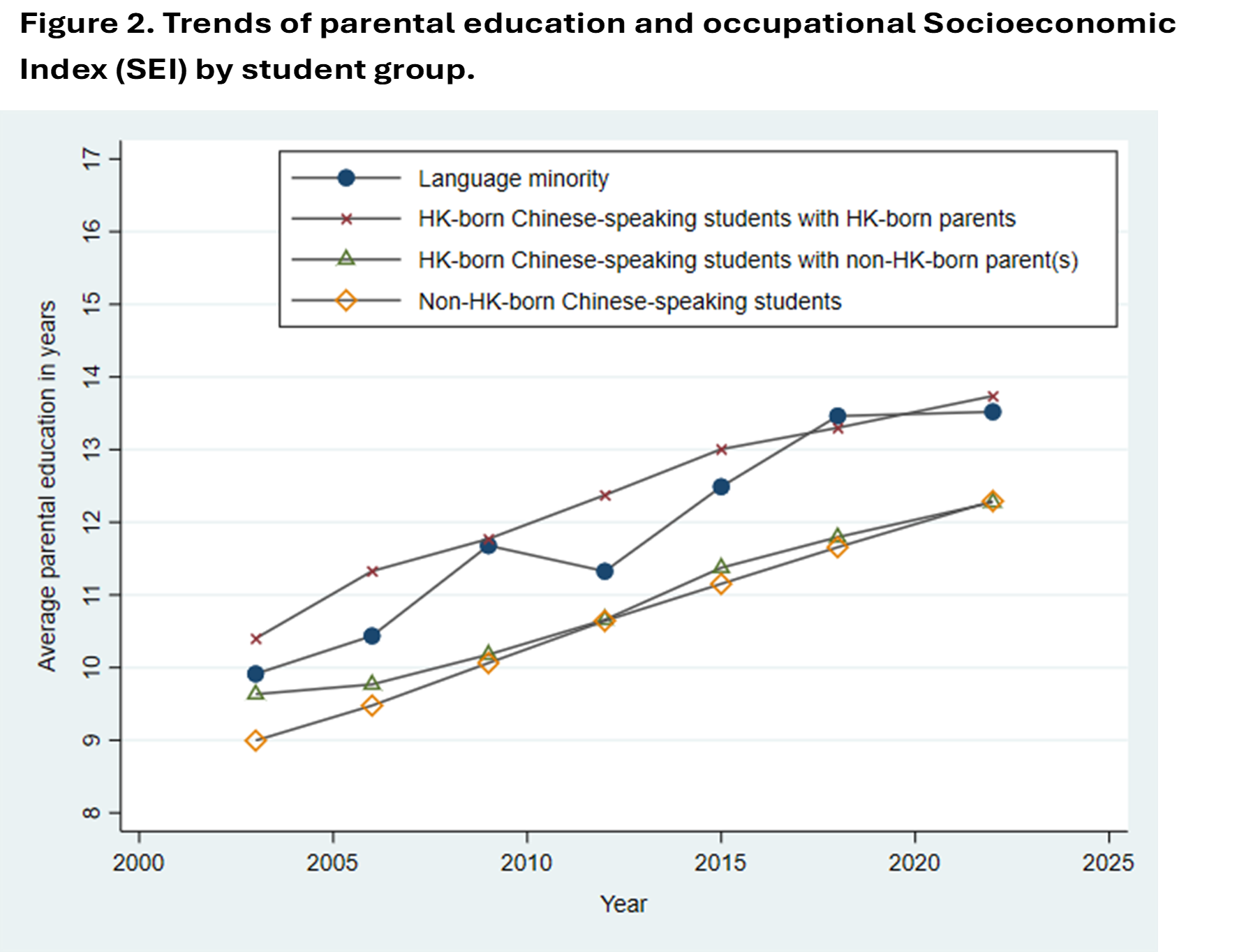

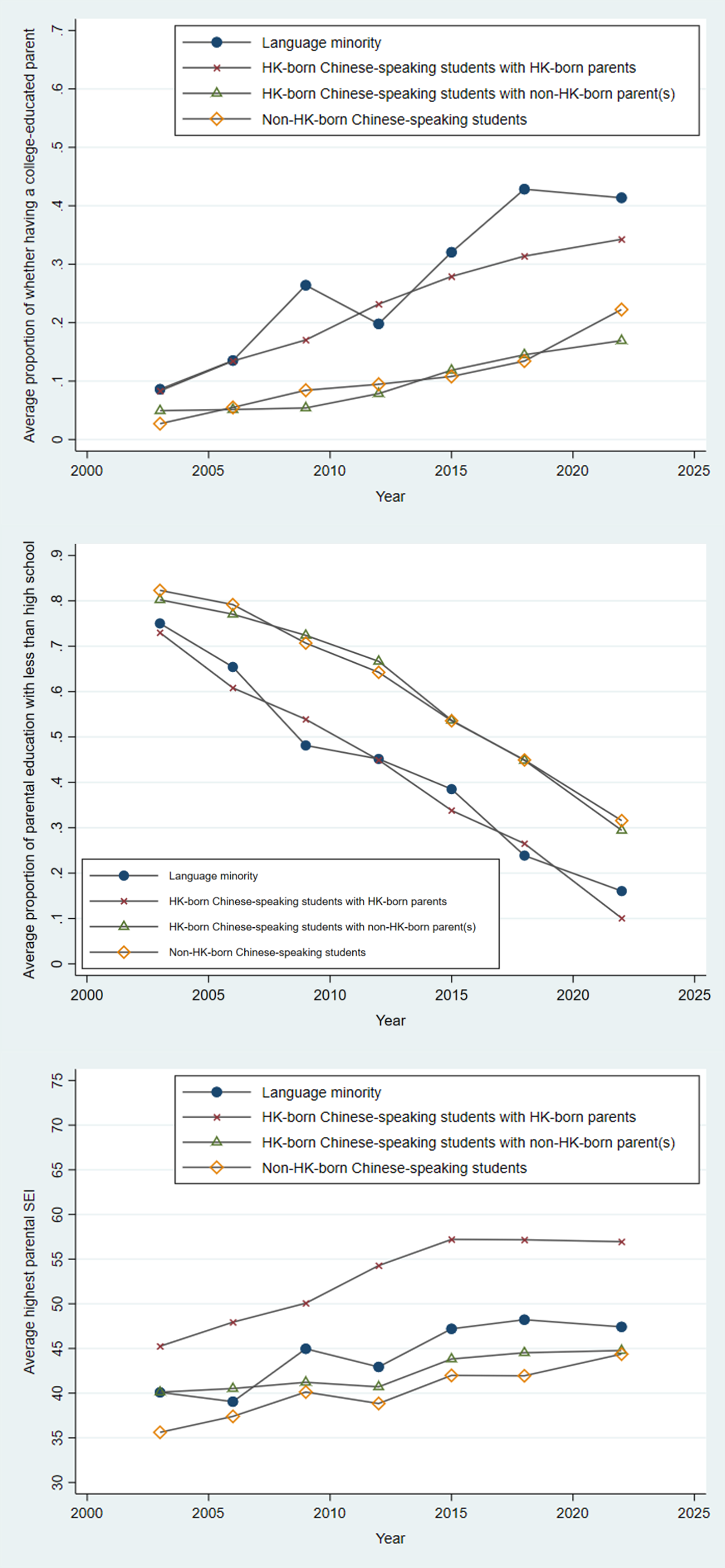

Figure 2 illustrates the trends in parental education and occupational SEI among the student groups from 2003 to 2022. Based on our statistical tests, it is evident that during the period of 2003-2012, parents of NCS students tend to have lower average years of education and occupational prestige compared to their locally born Chinese-speaking counterparts, whose parents are also locally-born, in 2003. Additionally, NCS students disadvantage in terms of parental occupational prestige further exacerbated from 2003 to 2012. However, our statistical tests reveal that the proportion of students with a college-educated parent and the proportion of students whose parents’ highest education level is below high school are comparable between the two student groups throughout the 2003-2012 period.

In the 2012-2018 period, NCS students also face disadvantages in terms of their parents’ highest education in years and highest parental SEI in 2012, relative to their locally born Chinese-speaking peers whose parents are also locally born. However, from 2012 to 2018, NCS students exhibit a more substantial increase in their parents’ highest education in years and the proportion of parents with a college degree. If parental education has a positive correlation with academic achievement, then the diminishing disadvantage in parental education among NCS students during the 2012-2018 period aligns with the closing achievement gap between NCS students and their locally born Chinese-speaking peers whose parents are also locally born within the same time frame.

During the 2018-2022 period, it is observed that although NCS students continue to have significantly lower levels of parental occupational prestige compared to their locally born Chinese-speaking peers whose parents are also locally born, they actually have a higher likelihood of having a college-educated parent in 2018. However, from 2018 to 2022, NCS students experience a significantly lower decrease in the probability of having parents whose highest level of education is below high school.

Figure 3 illustrates the patterns in average grade levels of 15-year-old students, as well as the likelihood of grade retention, across the survey years. The data indicates that NCS students consistently demonstrate lower levels of grade attainment, and a higher likelihood of grade retention compared to their locally born Chinese-speaking peers whose parents are also locally born throughout the three time periods. These gaps are statistically significant. Furthermore, our statistical tests, in conjunction with Figure 3 suggest a noteworthy improvement in NCS students’ average grade level attainment relative to their locally born Chinese-speaking peers whose parents are also locally born from 2012 to 2018. This finding aligns with the trends observed in Figure 1. The Improvement may be attributed to the implementation of the “Chinese Language Curriculum Second Language Learning Framework” by the Education Bureau in 2014. This framework specifically addresses the needs of students who struggle with the standard Chinese curriculum and reduces the likelihood of grade repetition.

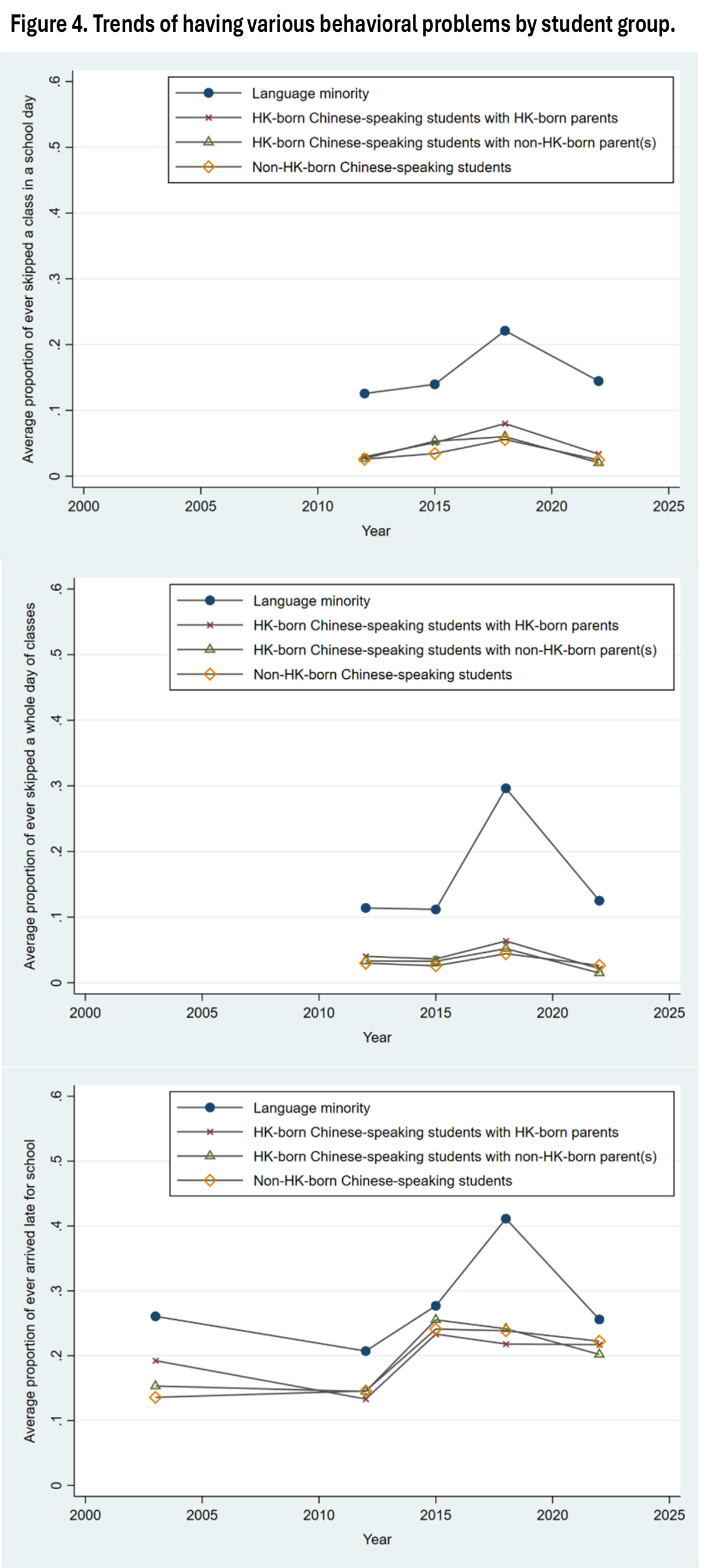

Figure 4 illustrates the trends in various behavioural problems among student groups from 2003 to 2022. In the period from 2003 to 2012, data are available only for students’ tendency to arrive late for school. The third graph in Figure 4, along with our statistical tests, indicates that NCS students have a higher probability of arriving late for school compared to their locally born Chinese-speaking peers with locally born parents. However, the gap does not show significant changes during the 2003-2012 period.

From 2012 to 2018, it is noted that in 2012, NCS students are more inclined to skip classes within a school day compared to their locally born Chinese-speaking peers with locally born parents. On the other hand, the likelihood of ever arriving late for school is similar between these two student groups. However, these gaps, or the absence thereof, do not exhibit significant changes from 2012 to 2018. Furthermore, despite NCS students having a similar likelihood of skipping an entire day of classes in 2012 as their locally born Chinese-speaking peers with locally born parents, the gap between them undergoes a significant increase from 2012 to 2018, to the point where it becomes statistically significant in 2018. This pattern may counterbalance the trend of narrowing the achievement gap between the two student groups during the period from 2012 to 2018. One possible explanation for the increased likelihood of NCS students skipping a whole day of class is their potential difficulty in adapting to the new methods of teaching Chinese under the new Learning Framework. It is plausible that these students have a less favourable classroom experience compared to before, despite the Learning Framework aiming to facilitate their Chinese language learning outcomes. This factor may contribute to the observed change in attendance behaviour.

During the timeframe spanning from 2018 to 2022, it is observed that although NCS students are more prone than their locally born Chinese-speaking peers with locally-born parents to display all three behavioural problems in 2018, the gaps in the likelihood of skipping an entire day of classes and arriving late significantly diminish from 2018 to 2022. In fact, by 2022, the disparity in the likelihood of arriving late is no longer statistically significant. This trend may be attributed to the shift in instructional mode from in-person to online during the COVID-19 global pandemic. It is important to consider that if behavioural problems are negatively linked to test scores, the reduction in gaps regarding arriving late for class and skipping an entire day of classes between 2018 and 2022 might have played a positive role in narrowing the achievement gaps between the two student groups during that specific period.

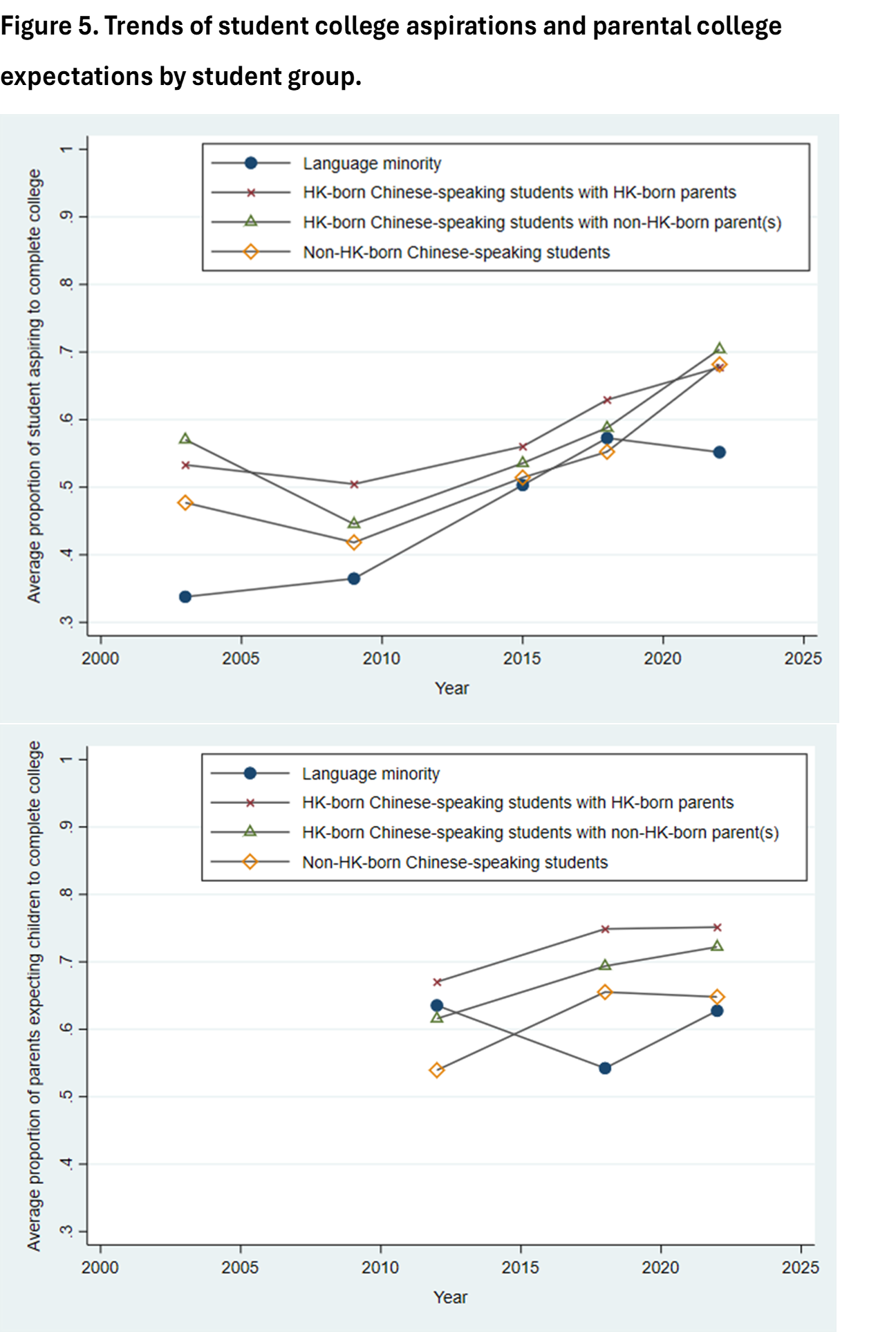

Figure 5 presents the trend of students’ college aspirations and parental college expectations. Regarding students’ college aspirations, we only have data available for 2003 and 2018, with no data for 2012. Therefore, we will focus on the change between 2018 and 2022. Our findings indicate that in 2018, NCS students have a lower likelihood of holding a college aspiration compared to their locally born Chinese-speaking peers whose parents are also locally born, and this gap remains stable between 2018 and 2022.

Moving on to parental college expectations, since we lack data for 2003, we will examine the trend between 2012 and 2018, as well as between 2018 and 2022. According to our statistical tests, although NCS parents and parents of locally born Chinese-speaking students whose parents are also locally born have similar educational expectations in 2012, NCS parents’ college expectations significantly decline from 2012 to 2018 in comparison to their reference group. As a result, the gap between the two groups becomes suggest that parental college expectations may have had a countervailing effect on the observed narrowing academic achievement gaps between 2012 and 2018 but potentially made a positive contribution to closing the achievement gaps between the two groups from 2018 to 2022.

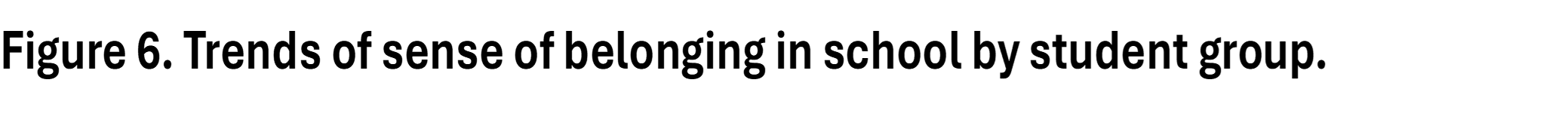

Figure 6 displays the trends of students’ sense of belonging in school based on student groups. Our findings suggest that students’ sense of belonging remained relatively stable between 2003-2012 and 2018-2022. However, there was a substantial decline in students’ sense of belonging from 2012 to 2018. And, this decline was comparable between non-Chinese speaking (NCS) students and locally-born Chinese-speaking students whose parents were also locally born.

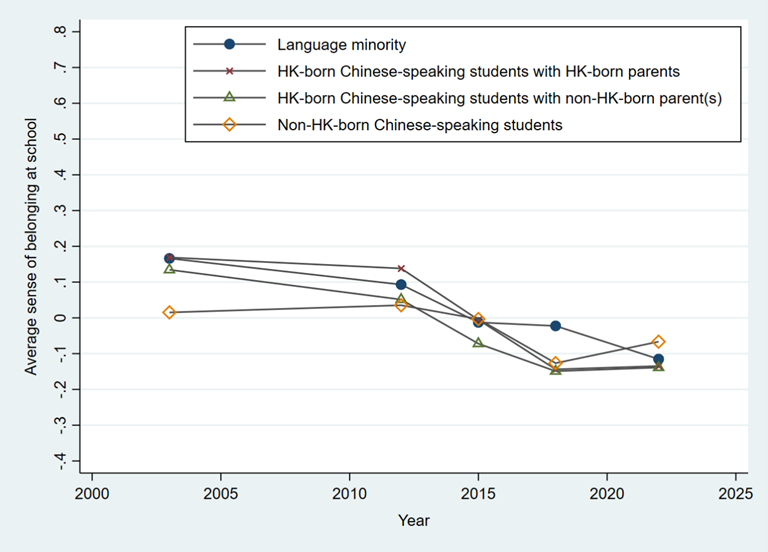

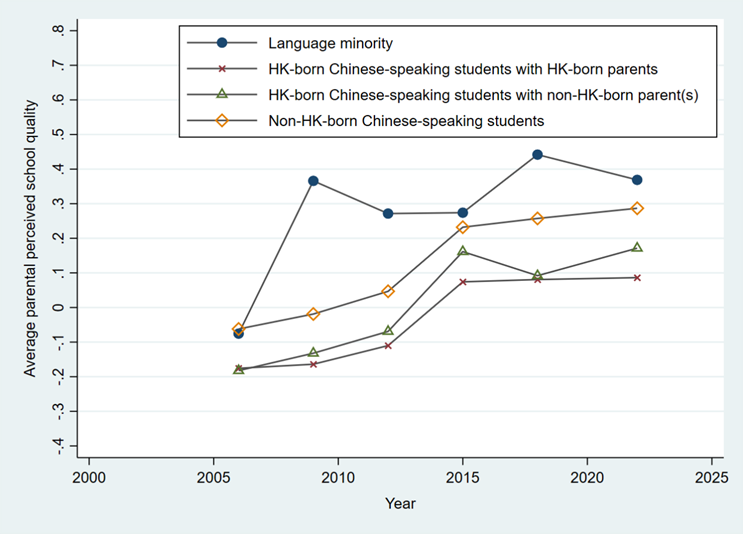

Figure 7 illustrates the trends of parental perception of school quality based on student groups. As we lack data for 2003, we will focus on the periods of 2012-2018 and 2018-2022. Our statistical findings indicate that NCS parents consistently perceive their children’s schools as having a significantly higher level of quality compared to parents of locally born Chinese-speaking students whose parents are also locally born throughout the entire study period. Moreover, the gap between the two groups remains stable between 2012 and 2018, as well as between 2018 and 2022.

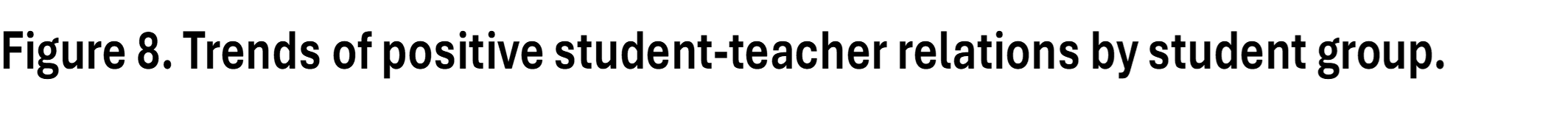

Figure 8 depicts the trends of positive student-teacher relations based on student groups. Since we have data only from 2003 to 2012 for this variable, we solely focus on the trends within this period. Our statistical findings reveal that in 2003, NCS students exhibit similar levels of positive student-teacher relations compared to their locally born Chinese-speaking peers whose parents are also locally born. Furthermore, NCS students experience a significant improvement in positive student-teacher relations from 2003 to 2012 relative to the reference group. However, by 2012, the levels of positive student-teacher relations were still comparable between the two student groups. If positive student-teacher relations have a positive correlation with students’ academic achievement, the observed changes in the gap between the two groups in terms of positive student-teacher relations from 2003 to 2012 actually counterbalance the increased disadvantage in academic achievements among NCS students during this time period.

This policy brief highlights two significant patterns in the test scores of NCS students compared to their locally born Chinese-speaking peers whose parents are also locally born. Firstly, NCS students consistently scored significantly lower than their locally born counterparts in all three test domains in 2003, 2012, 2018, and 2022. Secondly, the gaps between the two student groups in all three domains experienced a significant increase from 2003 to 2012, followed by a significant reduction in the gaps in science and reading test scores between 2012 and 2018, and remained stable from 2018 to 2022.

Our analysis of potential explanatory factors for these gaps suggests that between 2003 and 2012, NCS students’ significant improvement in positive student-teacher relations compared to their locally born Chinese-speaking peers may have counterbalanced the increased disadvantage in their math test scores.

During the period from 2012 to 2018, our analysis indicates that NCS students’ increased parental educational attainment and improved grade level attainment relative to their locally-born Chinese-speaking peers whose parents are also locally-born may have contributed to the narrowing achievement gaps in science and reading. However, the increase in the likelihood of NCS students skipping a whole day of class and the decline in parental college expectations compared to their locally born Chinese-speaking counterparts whose parents are also locally born may have counteracted the narrowing achievement gaps in science and reading between the two student groups.

The improvement in grade level attainment suggests that the “Chinese Language Curriculum Second Language Learning Framework” implemented in 2014 was effective in increasing students’ learning outcomes in key subjects. This framework appears to have achieved its aim of enhancing academic performance. However, the data also indicates that NCS students may have faced more adaptation challenges and a less favourable classroom experience under this new “Learning Framework”. This could have contributed to an increase in behavioural problems among them. The contrasting outcomes highlight the need to carefully evaluate the implementation and impacts of such curricular reforms, ensuring they address the unique needs and experiences of diverse student populations.

From 2018 to 2022, our analysis indicates that NCS students, when compared to locally born Chinese-speaking students whose parents are also locally born, demonstrated a reduced tendency of arriving late for class and skipping entire days of classes. Moreover, their parents’ expectations of attending college increased in comparison to their locally born Chinese-speaking peers whose parents are also locally born. These factors potentially contributed to the narrowing of achievement gaps in science and reading between the two student groups.

It is important to note, however, that this trend may be partially attributed to the shift in instructional mode from in-person to online during the COVID-19 global pandemic. This change in the learning environment may have had a differential impact on the two student groups, and the observed improvements may not be sustainable once the learning environment returns to a more traditional, in-person format. The findings highlight the need for continued monitoring and evaluation of the educational outcomes and experiences of diverse student populations after the end of the COVID-19 global pandemic. Targeted interventions and support may be necessary to ensure equitable and lasting improvements in student performance and engagement.

Future research should employ formal statistical modelling to determine the extent to which these factors contributed to or counteracted the observed changes in test scores across the periods of 2003-2012, 2012-2018, and 2018-2022.

Notes

[1] Census and Statistics Department of Hong Kong SAR. 2022. “Thematic Report: Ethnic Minorities.” Retrieved (https://www.census2021.gov.hk/doc/pub/21c-ethnic-minorities.pdf).

[2] Law, Kam-Yee, and Kim-Ming Lee. 2012. “The Myth of Multiculturalism in ‘Asia’s World City’: Incomprehensive Policies for Ethnic Minorities in Hong Kong.” Journal of Asian Public Policy 5(1):117–34. doi: 10.1080/17516234.2012.662353.

Law, Kam-Yee, and Kim-Ming Lee. 2013. “Socio-Political Embeddings of South Asian Ethnic Minorities’ Economic Situations in Hong Kong.” Journal of Contemporary China 22(84):984–1005. doi: 10.1080/10670564.2013.795312.

[3] Yan, Mingren. 2010. Postwar Hong Kong Education (in Chinese). Hong Kong: Academic Professional Library Centre.

[4] International schools in Hong Kong generally adopt English as the main medium of instruction and are not subject to the medium of instruction policy set by the Hong Kong government.

[5] Loh, Elizabeth Ka Yee, and On Ying Hung. 2020. “A Study on the Challenges Faced by Mainstream Schools in Educating Ethnic Minorities in Hong Kong.” Retrieved (https://www.oxfam.org.hk/tc/f/news_and_publication/1414/content_24743en.pdf).

Oxfam Hong Kong. 2016. “Survey on the Enhanced Chinese Learning and Teaching Support for Non-Chinese Speaking Students in Primary and Secondary Schools.” Retrieved (https://www.oxfam.org.hk/tc/f/news_and_publication/1414/content_24743en.pdf).

[6] OECD. 2005. PISA 2003 Technical Report. Paris: PISA, OECD Publishing.

[7] Dong, Hao, and Yu Xie. 2023. “Trends in Educational Assortative Marriage in China Over the Past Century.” Demography 60(1):123–45. doi: 10.1215/00703370-10411058.

Room 204, Ho Tim Building, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shatin, N.T. Hong Kong

(852) 2603 6850

©2023 ReCEPD, CUHK. All rights reserved. Powered by Techcomm.